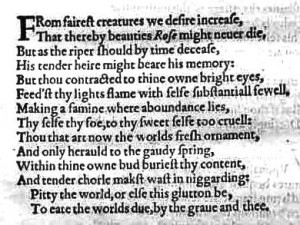

One of the incidental pleasures of reading Shakespeare’s sonnets is finding rhymes that give us clues about Elizabethan English. One of these occurs in the first four lines of the entire collection:

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

“Die” and “memory” are clearly not “eye rhymes.” In Shakespeare’s day, these two vowels would have been pronounced with a somewhat closer pair of vowels, probably something like ɘi for “die” and i: “memory.” So this would have been a more plausible oblique rhyme than it is today (for most American and British accents).

Such wordplay has been an excellent tool for historical linguists, validating important hypotheses about the Great Vowel Shift, the pronunciation of Middle English and other developments. So I sometimes wonder if, hypothetically speaking, historical linguists hundreds of years from now could deduce anything important from rhymes in our era.

Of course, it’s likely that such scholars will have far, far more written and recorded evidence of how their ancestors spoke than we do. But if, tragically, the entire internet were wiped clean and some future prescriptivist dictator were to destroy all writing about linguistics, would rhymes reveal anything about 21st-Century English speakers?

It likely depends, of course, on how much the language changes. One would also have to rely mostly on song lyrics, since rhyming poetry is not exactly the dominant literary form of the 2000’s. And although I can’t say what kind of pronunciations 25th-Century English speakers would find unusual, I can think of a few examples of lyrics that say something interesting about particular dialects of English.

Take, for instance, this snippet from Kanye West’s “Gold Digger:”

Eighteen years, eighteen years

And on her 18th birthday he found out it wasn’t his

West here rhymes “years” and “his,” because in some varieties of African-American English, the two vowels in these words are nearly neutralized in phrase-final or emphatic positions. The vowel in “his” is tensed and becomes something of a centering diphthong along the lines of iɪ, making it sound quite close to the vowel in “years.”

Of course, you would need more evidence to actually deduce this. Technically, this rhyme might also work for certain British accents, but for the opposite reason: the vowel in “years” can become a long monopthong with a similar quality to “his” (i.e. ɪ:). Which points out the main caveat of relying on rhymes: they can never serve as the sole piece of evidence in detective work like this.

Can anyone think of other contemporary lyric rhymes that suggest salient things about English today?