Annie Minoff has written a fascinating, in-depth piece on African American English over at WBEZ in Chicago. It’s worth reading in its entirety, but the main thrust of the article is that within African-American English one can find numerous regional accents that are recognizably distinctive.

This is something that anyone who has lived in a Northern or Western American city probably understands intuitively. New York City African-Americans, after all, often raise the THOUGHT/CLOTH vowel just as other New Yorkers do (i.e. the legendary “aw” in “cawfee”); Philadelphia African-Americans, meanwhile, often front the vowels in GOAT and GOOSE much like their Irish-American, Jewish-American and Italian-American counterparts. It would be fairly improbable for a single ethnolect to remain monolithic across hundreds of American cities.

That latter feature (u-fronting), by the way, seems true of Baltimore AAE as well, as linguist Cara Shousterman discussed in this excellent article on the Black English of that city (also worth a read):

Probably one of the most noticeable features of Baltimore African American English is what linguists call u-fronting, where the sound in a word like “do” gets pronounced as “dew”.

So why, you might ask, do people still think of AAE as being “uniform.” Minoff quotes the great American linguist Walt Wolfram, who suggests that some of the limitations and biases of early AAE studies may have played a role on this perception:

“In a sense,” [Wolfram] explains, “it was sort of an exotic other. Most early researchers who did research on AAE, like Labov and myself, were white. And so we came into these communities as people who had grown up in segregated situations. I would say that that was reflected in some of the things [we noticed] … I think we overlooked our own biases in terms of seeing regionality”

This is probably true to some degree. But I wonder if Wolfram is being a bit too hard on himself here. It is logical to think AAE may have actually been somewhat more uniform forty years ago than it is now.

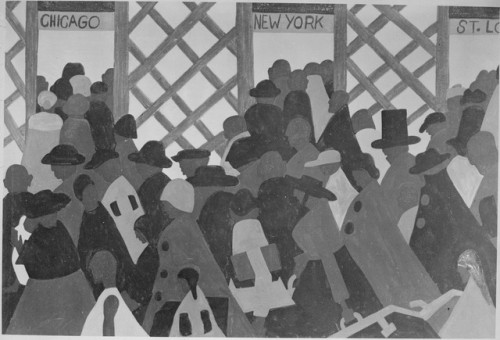

Some of the anecdotes from Isabel Wilkerson’s brilliant The Warmth of Other Suns imply that the Southern-inflected dialect we think of as “African-American English” was part and parcel of the “great migration” of African-Americans from the South between World War I and the 1970s. After all, African-Americans who had lived in the North for generations before this tended to be just as distrustful of this new dialect as Northern whites were:

It turned out that the old-timers were harder on the new people than most anyone else. “Well, their English was pretty bad,” a colored businessman said of the migrants who flooded Oakland and San Francisco in the forties, as if from a foreign country. To his way of looking at it, they needed eight or nine years “before they seemed to get Americanized.”

Point being, speakers of AAE in the early 1970s would have usually been at most a generation away from the South. It’s unsurprising that several decades down the road the surrounding linguistic environment has encroached somewhat more upon this ethnolect (while older forms of Northern/Western African-American English have perhaps merged with it).

So it’s worth wondering how much further this unique dialect will be eroded. Will AAE survive another hundred years in the Northern Cities? Or will it be subsumed by older local dialects? Conversely, will some older local dialects lose out to AAE?